MID-Atlantic Power Pathway and all of PJM’s “backbone” projects in the news:

She’s worried about a larger line rising in the shadow of her house. If the poles somehow get knocked over, “Where’s that line going to fall? That line’s going to fall in my living room.

That’s Farah Morelli’s question. She’s a regular person who woke up one day with a monstrously large transmission line planned literally in her back yard. That’s usually the most effective way to get someone to learn about transmission. It’s a steep learning curve, and what I’ve found in my work with people in the path of proposed transmission is that once they start looking, they find a disturbing fact: Utilities propose transmission lines not because they’re “needed” but that they’re wanted, wanted to increase their ability to transmit and SELL cheap power in areas where it’s higher cost, and make a bundle in the process. It’s not that people don’t have electricity (and high price is the best instigator of conservation), but it’s that people want more and want it cheaper and the utilities which make $$$ from that equation want to make it happen.

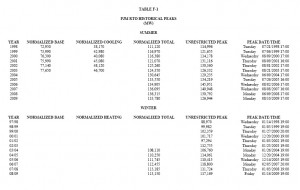

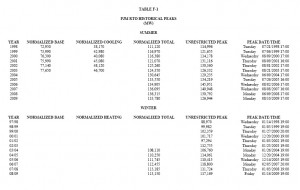

HERE’S THE REALITY — The PJM 2010 Load Forecast Report and the Monitoring Analytics “PJM 3Q State of the Market” report show that this market decline isn’t anything new and that it’s not going away anytime soon. The PJM market peaked in 2006:

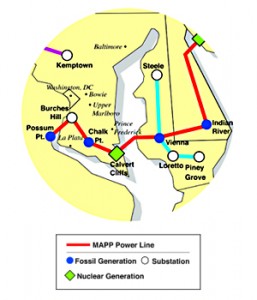

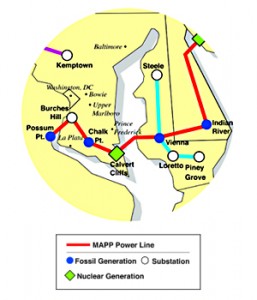

Today’s News Journal article is a start at pulling it all together, taking a look at the bigger picture, and that bigger picture is what these transmission lines are all about. Three lines were proposed together, the Potomac Allegheny Transmission Highline (PATH), the Mid-Atlantic Power Pathway (MAPP) and the Susquehanna-Roseland line. These aren’t just transmission lines, they’re BIG HONKIN’ ELECTRICAL AUTOBAHNS, quad (or now maybe tri?) bundled 500kV lines. Like WOW. HUGE!

Here’s today’s article:

Economy, increased efficiency, carbon consciousness delay projects

By AARON NATHANS • The News Journal • January 24, 2010

It was Delaware’s electric doomsday scenario: Living room lights would go dark unless Delmarva Power could import electricity to a growing population.

Just a few years back, power companies lined up to design hulking new lines to bring power from the Midwest, where 56 percent of electricity is generated by coal-burning plants.

Those plans included building a high-voltage line from Virginia to New Jersey that would have unfurled across the heart of Delaware, helping assure reliable power to the state — and costing customers of Delmarva Power $1.2 billion.

But the world changed — seemingly overnight.

Now regional power grid operator PJM Interconnection is dialing back its projections of future energy use amid a sluggish economy, increases in energy efficiency and the new economics of energy in the age of carbon consciousness.

That has set off a domino reaction of delays in power companies’ plans to build those lines, as PJM reassesses when the lines will be needed, if they’re needed at all.

The reassessment is a chance to wean the country off fossil fuels and build the infrastructure around locally sited renewables without having to erect giant electrified structures in peoples’ backyards, said Carol Overland, an attorney representing opponents of a proposed large power line in New Jersey.

“It’s a very good shift. Culturally, that’s a shift we need to make,” Overland said. “It gives us an opportunity to do it differently.”

Although Delmarva has rights of way through most of its planned Delaware route, it is working to acquire the rights to build on long stretches of land on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, through farms like the one owned by Libby Nagel, of Vienna. Portions of the farm have been in her family for 100 years. She has been fighting the line, saying it will interrupt irrigation and get in the way of low-flying pesticide spray planes. She is concerned Delmarva will invoke eminent domain to force the line onto her property.

“This transmission line is about them bringing cheap coal-fired power in here,” Nagel said, arguing it’s more about profits than reliability. “They say we’re going to benefit. But it is a transmission line. That’s all it is.”

The line, known as the Mid-Atlantic Power Pathway, was proposed in 2006 by Delmarva Power’s parent company, Pepco Holdings, Inc. It would run from Virginia to Maryland, across the Chesapeake Bay and end at the Indian River Power Plant in Millsboro.

The line originally was to continue on to the nuclear power plant in Salem, N.J., but that leg was pushed back last summer after PJM ran computer models and found that reliability issues in Delaware have eased due to a downturn in electricity usage.

Last month, those models showed a wider shift, which led PJM to tell two power companies that portions of its Potomac-Appalachian Transmission Highline would not be needed in 2014 as scheduled. The “PATH” project, sponsored by Allegheny Energy and American Electric Power, would link West Virginia to the Frederick, Md. area.

The Delmarva line would receive power from this line indirectly. So when the PATH line was delayed, Delmarva asked the Maryland Public Service Commission to delay its own application.

As utilities find ways to reduce peak usage among their users, renewable energy is growing faster than anyone anticipated, said Steven Herling, vice president of planning of PJM. New and anticipated pollution restrictions are quickening the demise of older coal plants, he said.

“It’s a huge challenge to figure out which of those impacts is going to be more pressing as we move forward,” Herling said.

PJM’s review, expected to be completed this summer, could lead to small changes of the routes of the proposed lines, tweaks to construction dates, or “an entirely different set of solutions,” Herling said. PJM covers 13 states and the District of Columbia in the Mid-Atlantic, South and Midwest.

The review will take into account data like a projection from the U.S. Energy Information Agency that energy consumption will grow at a rate of 1 percent per year through 2035. That nearly cuts in half the same projection made in 2005, which foresaw 1.8 percent annual growth.

America’s energy future is changing, said Lester Lave, professor of economics at Carnegie-Mellon University.

Beyond the short term, economists are projecting a much lower rate of economic growth and consumption than what had been projected before, he said.

The price of coal-fired electricity will also go up, Lave said. Coal has traditionally been considered cheap, but with new pollution standards and the potential for a national carbon allowance trading program, coal producers will face higher production costs, he said.

Another big reason, Lave said, is efficiency. There are new standards for appliances and lighting that require using less electricity, and there’s additional opportunity to save energy in homes and businesses. He added that smart meters will help reduce usage during the hottest and coldest days, a major driver of electricity usage.

“We’re not talking about the recession. We’re talking about something more permanent,” Lave said.

Bob Dobkin, spokesman for Pepco Holdings, said his company’s delay is merely procedural, to allow PJM to react to the new data and make new projections.

In the meantime, Pepco will continue designing the route and the power line, working on permitting, and doing environmental studies. Dobkin defended the need for the line, saying the Delmarva Peninsula has very high prices to guarantee electric reliability. The peninsula only has transmission coming from the north. It needs a stronger backbone transmission system that provides a southern link to additional energy sources, he said.

It’s unclear whether the NRG-Bluewater Wind offshore wind farm, designed to provide locally generated power to the Delmarva Peninsula, will be built as planned by 2013, or what the price of coal will be down the road, Dobkin said. And it’s unclear whether the planned expansion of the nearby Calvert Cliffs nuclear plant, which would add a third unit, will occur on schedule, Dobkin said.

“Do people want to have their lights on or not?” he said. “Or do you not want that, because there’s coal-fired generation?”

Delmarva is participating in a state-sponsored effort to identify its future energy sources, including the question of whether it should buy additional renewable energy, and whether a natural gas-fired plant should be constructed in Sussex County.

Willett Kempton, an associate professor at the University of Delaware, noted there are 1,500 megawatts worth of offshore wind projects, enough to power 675,000 homes, that state governments have gotten behind. In recent months, eastern governors have gone on record as opposing east-west power lines, and supporting an offshore, underwater transmission line to link the offshore projects, he said.

Many coal plants have been canceled since 2005, and “at the same time, you’ve got wind growing like crazy,” Kempton said.

Farrah Morelli, of Delmar, Del., already has a Delmarva power line in her backyard. She has six children, ages 2 to 10, and says she doesn’t want them playing in the shadow of the larger line.

She’s worried about a larger line rising in the shadow of her house. If the poles somehow get knocked over, “Where’s that line going to fall? That line’s going to fall in my living room.”

Leave a Reply