Clean Power Plan — MPCA Meetings

March 9th, 2016

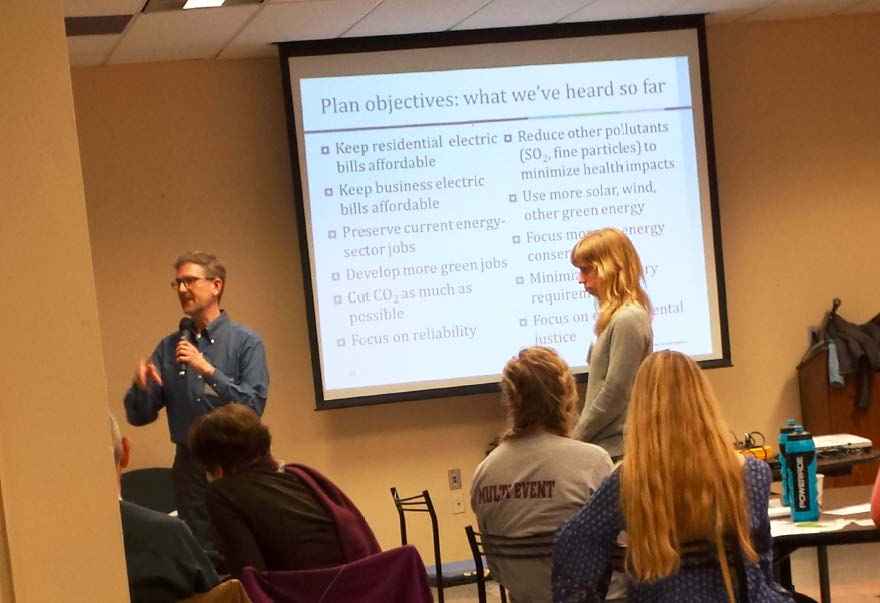

Last night at the Urban League, the MPCA held a meeting, a “listening session” about the proposed Clean Power Plan as a prelude to its rulemaking.

TONIGHT IS ANOTHER MEETING:

MPCA Clean Power Plan Listening Session

Wednesday, March 9, 2016

5:30 p.m. – ? At least 8 p.m.

Cornerstone Plaza Hotel

401 6th Street S.W.

Rochester, MN

The MPCA has been holding ‘listening sessions,” a/k/a meetings, and has info on its site:

Clean Power Plan: Rulemaking in Minnesota

Here’s the federal plan, now on hold at order of the court:

Clean Power Plan (U.S. EPA)

I very much do like that they’re going forward, despite the federal stay, because it is going to take some time to ramp up efforts.

Here’s the handout I brought to that meeting. I ran out, only about 1/4 of the room covered, so that means there were at least 80 people there.

On the other hand, there are a lot of things I take issue with.

One thing that’s discouraging to me is that this is called the “Clean Power Plan” but they have not made any attempt to separate out and prohibit burning of garbage and biomass, both very dirty by any definition. Incineration must be removed from the definition of “renewable.”

Another issue is that they’re NOT going to put together a rulemaking Advisory Committee, as provided by statute. I asked about this last night and they verified it.

Instead, what they’re doing is gathering the same ol’ same ol’ folks in an informal process, and they’re not going over a proposed rule prior to its being sent to the MPCA head (remember, there is no Citizens Board thanks to certain MN legislators) for release, and when it’s released, it’s too late for substantive changes. The MPCA was part of the crew, with DNR and EQB, that so badly mangled that silica sand rulemaking (ummmm, whatever became of that, anyway?). This does not bode well.

So now, on to tonight’s meeting, gotta do some prep.

And yes, that’s Frank “Coal Ash” Kolasch presenting. What a moniker!

Tonight’s gathering starts at 5:30 p.m. or so with an open house (coffee & cookies), and the presentation and “listening” starts at 6:30 p.m.

MPCA Clean Power Plan Listening Session

Wednesday, March 9, 2016

5:30 p.m. – ? At least 8 p.m.

Cornerstone Plaza Hotel

401 6th Street S.W.

Rochester, MN

Be there or be square!

Chesapeake’s McClendon dies!

March 3rd, 2016

Thanks to a “little birdie” for the heads up!

Thanks to a “little birdie” for the heads up!

The day after indictment of Chesapeake’s Aubrey McClendon, he crashes into bridge abutment on left side of road at “high rate of speed” and dies in a firey crash.

Energy pioneer McClendon dies in Oklahoma car crash a day after indictment

Ex-Chesapeake CEO Aubrey McClendon dead after car accident

McClendon remembered as energy ‘visionary’ despite controversy

Here’s the report that exposed his dealings to the world:

Special Report: Chesapeake and rival plotted to suppress land prices

He’s also made massive political donations, including to “friend of fracking” Hillary Clinton in 2008, and also $250k to the Swiftboaters. From Sourcewatch:

McClendon has donated to both Republican and Democratic political candidates, though most of his donations and his major donations have been to Republicans or Republican-associated groups, including the Republican National Committee, National Republican Congressional Committee and Oklahoma Leadership Council; [12] and 527 groups, most notably the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, to which he contributed $250,000 in 2004. [13]

But that’s not all — Chesapeake bought off Sierra Club during Carl Pope’s reign:

From Slate, about McClendon’s death and legacy:

Why Aubrey McClendon, the Fracking CEO Who Died in a Crash Wednesday, Was His Industry’s Perfect Symbol

Aubrey McClendon, the high-flying founder and former CEO of Chesapeake Energy, a pioneer of the fracking revolution, died Wednesday in Oklahoma City after his car hit a wall in at high speed. McClendon, 56, had been indicted Tuesday on federal charges of conspiring to rig bids on leases when he was CEO of the Chesapeake. According to the New York Times, he was supposed to be in court later in the day.

In his field, McClendon was victim both of his own success and of some familiar business and character flaws. Those who have seen Hamilton will recognize his particular American archetype: relentlessly aggressive, self-made, brilliant, a balls-out risk taker even when he had it made, tolerant of big losses, able to pick himself immediately after getting knocked down, a man of large appetites. And, also, it turns out, a little crazy. McClendon was of a personality type described by the psychologist John Gardner in his book Hypomanic Edge, one that you often see during booms and busts. You don’t need the hypomanic edge to succeed in America. But you might need it to succeed at scale, at national level, in a place as big and large as this.

After the Internet, fracking might be the most significant technological development of the last 30 years. The techniques of hydraulic fracturing have liberated, at low cost, immense amounts of oil and natural gas, lowering energy costs, turning the U.S. from an energy importer into an energy exporter. And McClendon was there right at the beginning. If you want to understand, read these two books by Wall Street Journal reporters: Greg Zuckerman’s The Frackers and Russell Gold’s The Boom: How Fracking Ignited the Energy Revolution.

Chesapeake—which, despite its name, is based in Oklahoma—is the second largest producer of natural gas in the U.S. McClendon founded it in 1989 with 10 people and built it into a Fortune 500 company thanks to its combination fracking and aggressive deal-making. With his wealth he acquired a magnate’s usual toys, including a chunk of the Oklahoma City Thunder.

But McClendon was undone by the type of behavior that is surprisingly common among people who have built large enterprises rapidly. Having built a huge fortune and a huge company, he leveraged it further and lived ever larger. As Reuters reported in a big 2012 investigation, McClendon bought a slew of high-end properties, used corporate jets for family travel, borrowed money against his holdings, and ran a hedge fund out of the company’s offices.

Such behavior can be tolerated or overlooked when a company is booming. But there’s much less margin for error when the markets turn against you. Fracking became such a potent technology that annual natural gas production in the U.S. soared by 40 percent between 2005 and 2015. Much of the natural gas found its way into power plants; between 2005 and 2015, the percentage of U.S. electricity derived from natural gas rose from 19 percent to 32 percent. But fracking has produced a glut. While there is a small and growing market for natural gas as a transportation fuel, particularly in bus and trucking fleets, there is a cap to domestic demand. And while you can easily export oil by piping it onto tankers, exporting natural gas requires the construction of enormously expensive import and export terminals, equipment, and specialized ships that can carry the cargo. Led by Chesapeake and its cohort, the U.S. vastly increased its production of natural gas without boosting its capacity to use or export it.

That was great for the U.S. economy. The supplies of cheap natural gas have helped lower emissions, boost air quality, keep power prices down, and provided an enormous competitive advantage to chemical plants and other industries that use natural gas as a feedstock or ingredient. But it has proven to be bad news for highly leveraged companies in the business of natural gas production, like Chesapeake.

Between May 2008 and May 2012, Chesapeake’s stock fell by about two thirds. And the falling stock took McClendon down with it. Rather than sell shares of the company he founded, he borrowed money with the stock as collateral. In 2012, margin calls forced him to sell big chunks of stock. As investigations mounted in the wake of the Reuters report, McClendon stepped down as CEO in January 2013.

Rather than sulk off and enjoy his still substantial wealth, McClendon almost immediately set up a new energy company, just down the street from Chesapeake’s headquarters. “We’re built to be opportunistic and bold,” the company, American Energy Partners, proclaims on its website. American Energy Partners raised boatloads of money from private equity investors to invest in natural gas production.

As McClendon was building his new company, however, federal prosecutors were building a case against him. The indictment charges that McClendon conspired with executives at another, unnamed company, to rig bids on natural gas leases. And reading between the lines, it seems like Chesapeake—the company he founded—had been cooperating with the investigation.

McClendon’s rapid rise and fall highlights a unique aspect of America’s historic economic development. It often takes bubbles to create new industries and build new industrial infrastructure in the U.S. And it often takes highly ambitious rogues to make those bubbles happen.

——–

NOTICE – PPSA ANNUAL HEARING 12/1

November 9th, 2015

Notice of the Power Plant Siting and Transmission Line Routing Program Annual Hearing

Issued: November 6, 2015

In the Matter of the 2015 Power Plant Siting Act Annual Hearing

Public Utilities Commission (PUC) Docket Number: E999/M-15-785

Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH) Docket Number: 60-2500-32901

Date: Tuesday, December 1, 2015

Time: 9:30 a.m.

Location: Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, Large Hearing Room, 121 7th Place East, Suite 350, Saint Paul, MN 55101

Bad weather? Find out if a meeting is canceled. Call (toll-free) 1-855-731-6208 or 651-201-2213 or visit mn.gov/puc

Hearing Description

The annual hearing is required by Minnesota Statute § 216E.07, which provides that:

Thecommission shall hold an annual public hearing at a time and place prescribed by rule in order to afford interested persons an opportunity to be heard regarding any matters relating to the siting of large electric generating power plants and routing of high-voltage transmission lines. At the meeting, the commission shall advise the public of the permits issued by the commission in the past year….

Note – No decisions about specific projects are made at the annual hearing.

Public Hearing Information

- Public hearings start on time.

- Arrive a few minutes early so you have time to sign in, pick up materials, and find a seat.

- Administrative Law Judge James LaFave will preside over the hearing.

- Public Utilities Commission and Department of Commerce staff members are available to answer questions about the Power Plant Siting Act processes and the projects.

- You may add verbal comments, written comments, or both into the record.

- Learn more about participating at a public hearing at http://mn.gov/puc/resources/meetings-and-hearings.jsp

- Judge LaFave will use information gathered at the public hearing and during the comment period to write a summary report for the Commission

Submit Comments

Topics for Public Comment:

- Any matters related to the site permit process for large electric generating power plants and routing of high-voltage transmission lines.

Comment Period: November 6, 2015 through January 5, 2016 at 4:30pm.

- Comments must be received by 4:30pm on the close date

- Comments received after comment period closes may not be considered

Online Visit mn.gov/puc, select Speak Up!, find this docket (15-785), and add your comments to the discussion.

If you wish to include an exhibit, map or other attachment, please send your comments via eFiling (see below) or U.S. Mail.

Please include the Commission’s docket number in all communications.

Filing Requirements: Utilities and state agencies are required to file documents using the Commission’s electronic filing system (eFiling). All parties, participants and interested persons are encouraged to use eFiling: mn.gov/puc, select eFiling, and follow the prompts.

Important Comments will be made available to the public via the Public Utilities Commission’s website, except in limited circumstances consistent with the Minnesota Government Data Practices Act. The Commission does not edit or delete personal identifying information from submissions.

Hearing Agenda

I. Introductions

II.Overview of Programs

A. Public Utilities Commission – Facilities Permitting and Public Advisor

B. Department of Commerce – Energy Facilities Permitting Unit

C. Role of Other Agencies

III. Projects Reviewed

A. Projects Permitted in 2015

B. Pending and Anticipated Projects

C. Electric Facilities Subject to Power Plant Siting Act

1. Generating Plants

2. Transmission Lines

IV. Public Questions and Testimony

V. Adjourn

How to Learn More

Subscribe to the Docket: Subscribe to receive email notifications when new documents are filed. Note – subscribing may result in a large number of emails.

- mn.gov/puc

- Select Subscribe to a Docket

- Type your email address

- For Type of Subscription, select Docket Number

- For Docket Number, select 15 in the first box, type 785 in the second box

- Select Add to List

- Select Save

Full Case Record: See all documents filed in this docket via the Commission’s website – mn.gov/puc, select Search eDockets, enter the year (15) and the docket number (785), select Search.

Project Mailing Lists: Sign up to receive notices and opportunities to participate in other dockets relating to specific projects in which you are interested (meetings, comment periods, etc.). Contact docketing.puc@state.mn.us or 651-201-2234 with the docket number, your name, mailing address and email address.

Minnesota Statutes and Rules: The hearing is being conducted according to Minnesota Statute 216E.07. Minnesota Statutes are available at www.revisor.mn.gov.

Project Contacts

Public Utilities Commission Public Advisor

Tracy Smetana – consumer.puc@state.mn.us, 651-296-0406 or 1-800-657-3782

Smoke gets in your eyes…

August 26th, 2015

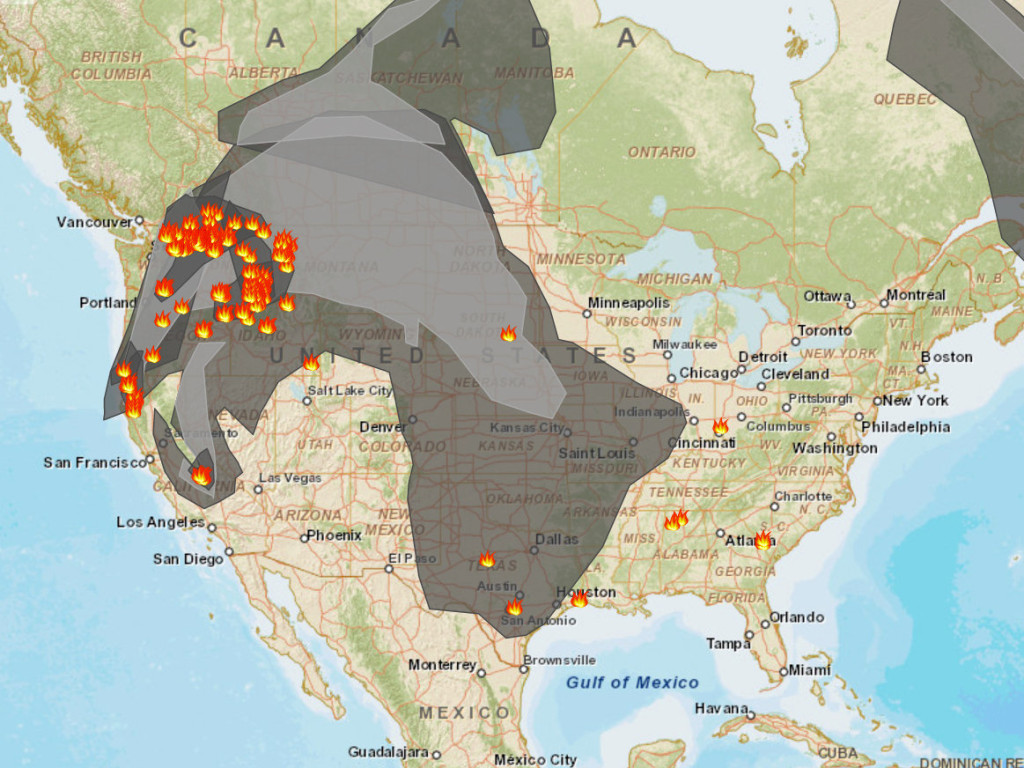

… and lungs and heart. This map from AirNow.gov via NPR shows the wide ranging impacts:

See Smoke From Wildfires Threatens Health in the West from NPR yesterday. Back when we had RED air quality warnings in Minnesota, a couple of months ago now, I was feeling it. But the last week or so, I’ve been waking up totally stuffed, headache, and it takes about an hour and a half to get my schnozz cleared out. We have no German Shepherds, and even though little one-coated Sadie does shed, and even though I nuzzled a cat day before yesterday, that’s not enough to cause this. Could it be seasonal allergies, which are admittedly worse with age (OH MY DOG, no German Sheperds is bad enough, but just breathing?)? I’m not convinced. This headache and being stuffed up isn’t my typical response, which tends to be runny eyes, sandpaper nose and sniffles. It’s got to be the fires.

See Smoke From Wildfires Threatens Health in the West from NPR yesterday. Back when we had RED air quality warnings in Minnesota, a couple of months ago now, I was feeling it. But the last week or so, I’ve been waking up totally stuffed, headache, and it takes about an hour and a half to get my schnozz cleared out. We have no German Shepherds, and even though little one-coated Sadie does shed, and even though I nuzzled a cat day before yesterday, that’s not enough to cause this. Could it be seasonal allergies, which are admittedly worse with age (OH MY DOG, no German Sheperds is bad enough, but just breathing?)? I’m not convinced. This headache and being stuffed up isn’t my typical response, which tends to be runny eyes, sandpaper nose and sniffles. It’s got to be the fires.

Meanwhile, I know a few folks who live out there, and in addition to having to evacuate and be on alert, others with relatives heading out to fight the fires, there are more subtle affects, where it’s showing up unbidden in photography jobs, an added interference with chemo for cancer, and a hazard for COPDers.

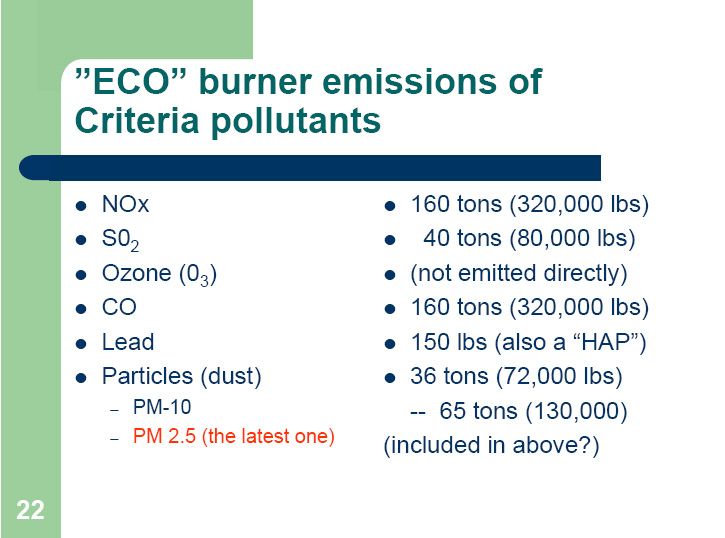

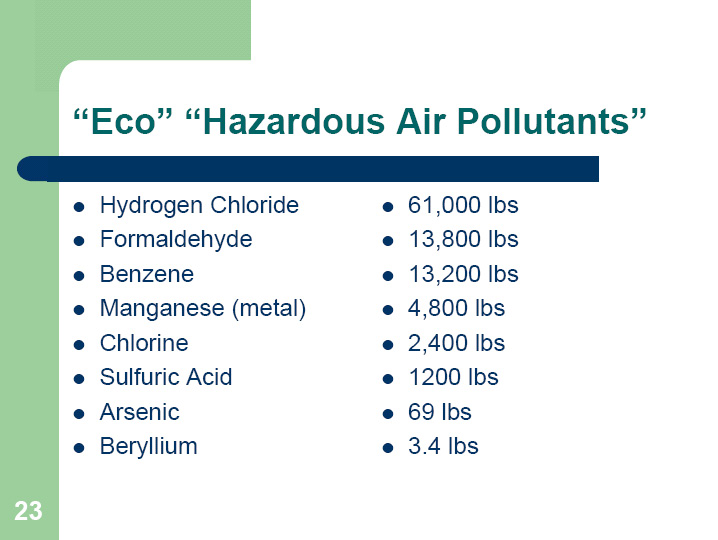

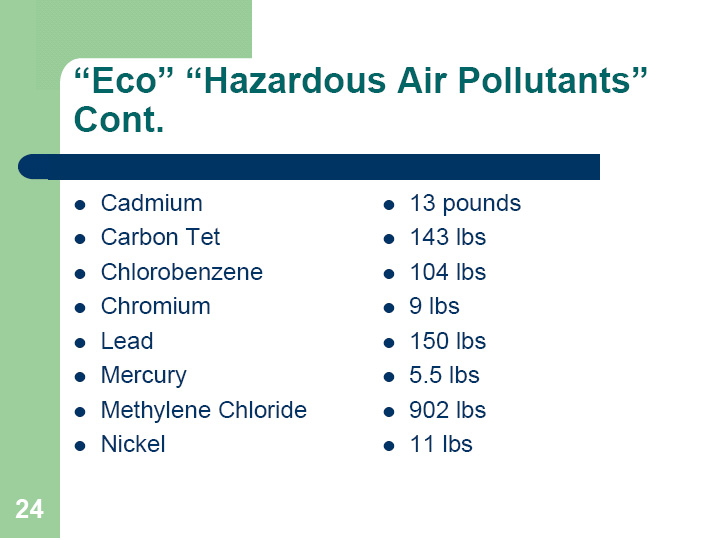

Here’s the chart of emissions for the Midtown Burner, from Saying NO to Midtown Burner Permits prepared by Alan Muller based on the Midtown Burner proposed air permit for the roughly 38MW biomass plant that was to burn “clean” trees in a much smaller amount than these wildfires across the west:

So if these are the numbers for the small biomass burner, what are the emissions for these wildfires? Is anyone doing testing in the plumes for what people are exposed to? There’s the emissions as above of things like formaldehyde that come from “clean” trees, the tremendous Particulate Matter, but what about all the other things too that are burned in these fires, like plastics, tires, creosote and penta poles? I’m not finding anything, and it seems this is something that should be done by the Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, etc., state environmental agencies. There should be active warnings to people to wear masks outdoors, and indoors to filter the air. We have a HEPA filter for every room, but we’re not normal. The impacts of breathing this air will be felt immediately by some people, but there’s a high likelihood that impacts are cumulative and/or take time to develop. Protection now is crucial.

Muller: Time to think about…

August 23rd, 2015

Commentary by Alan Muller, Green Delaware, in today’s Delaware State News:

Commentary: Time to think about Delaware’s Peterson, Coastal Zone Act

So what about this Coastal Zone Act? What makes it special and worth preserving.

Alan Muller is Executive Director of Green Delaware.