Xcel & GRE bring CapX2020 to PUC

September 22nd, 2006

CapX2020 moving right along… Here’s the map that wouldn’t load yesterday:

(guess not…)

Technically, it’s Xcel and Great River Energy bringing us this line (GRE’s one of those who also brought us Big Stone)(and then there’s Big Stone Wind, but that’s for another day…), but we know this big web of transmission lines across the state wouldn’t be possible without the acquiescence of those who signed the June 2003 TRANSLink deal and paved the way for the 2005 Transmission Omnibus Bill from Hell. The horse is out of the barn, though we can clearly see the horses’ asses.

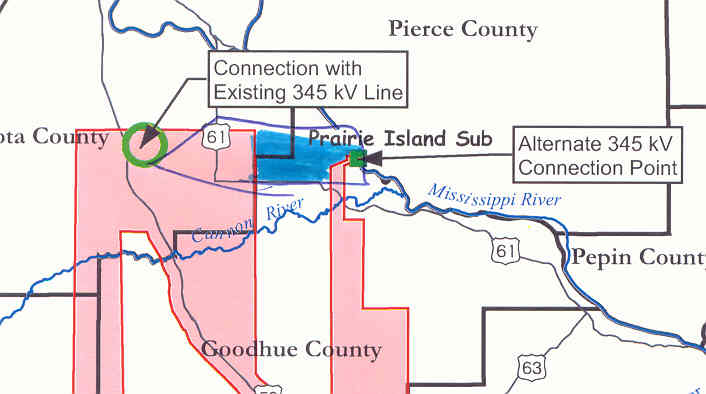

OK, look above at that horizontal blue line across the state, just south of the cities? Then it goes down and east? That’s the “Brookings” to “Hampton Corners” (Prairie Island) and then “SE Metro” to LaCrosse” which is really on big export line from SW Minnesota (Big Stone II) to Wisconsin. At the MAPP meetings I go to sometimes (when it’s interesting stuff, they always schedule way far away), this has always been the SW to PI and PI-Roch-Lax, and suddenly it changed to “Hampton Corners” and in the Notice Plan handouts, they tried to present it as two separate lines. Right…

Here’s the maps as they present them now: MAPS

Here’s the map that drives me crazy, the logical link between Hampton Corners and Prairie Island is missing.

Notice that at the green circle on the Left, it says “Connection with Existing 345kkV line.” OK, so you connect with that line, then what? Well, look at that map above, it goes out to Wisconsin. How do you get to WI from there? You either go southeast, along that new corridor shown on the map along 52, where there is no line, no easements, and which is contrary to Minnesota’s non-proliferation theory where you have to use existing corridors… OR you do the logical link, where at Hampton Corners, they’re connecting with the existing line, well DUH, as they’d said in all prior iterations, it’s a line that connects to PI, so you run along that pre-existing corridor, as requred under the PEER decision, over to Prairie Island. BUT THEY LEFT THAT PART OFF THE MAP, AND LEFT THOSE FOLKS ALONG THAT CORRIDOR OUT OF THE NOTICE PLAN, LEFT THEM OUT OF THE LOOP!!!! So I had a few go-rounds with Koppendrayer, he was very invested in keeping it separate. BUT, thankfully I’d put that map above in my Comment so they could look at it and see the big plan. Nickolai got it and acknowledged it and made the Motion to amend to include that corridor between Hamption and Prairie Island along the existing 345kV corridor.

You know, this isn’t rocket science, it’s just connect the dots. Commerce’s Steve Rakow may think being able to connect the dots is “conspiracy theory,” so he says, but I’d rather be able to track trajectory than live in delusion land. And what does he know — he’s the one who said that the line went through “Red Wing Township” and “Winona Township” and sure didn’t want to hear otherwise. OK, fine, put that in writing! See fn 5 and my Comments on p. 5-6 in the Staff Briefing Papers. Even Xcel agreed it’s CITY OF Red Wing and Winona.

All in all, not a bad time. Got acknowledgement that “it’s all connected.”

And it was very obvious that many parties were missing at the table yesterday — those who did the TRANSLink deal, those who ushered the 2005 Transmission Bill from Hell through the legislature, those who made this CapX2020 nightmare possible. Thanks guys… this legacy, 50+ years of infrastructure commitment down the wrong road, will far outlast you.

Now, how to stop this bulk-power-transfer nightmare? There’s a little time before the application is filed.

That means it’s a good time to read Powerline again for some inspiration and focus… If you don’t have it, there’s usually a couple at www.abebooks.com.

Excerpt from POWERLINE: THE FIRST BATTLE OF AMERICA’S ENERGY WAR

________________

Foreword by Senator Tom Harkin

A local rebellion occurred in several rural countries of west central Minnesota in the mid- to late 1970s over the decision to locate an electric powerline through good farmland there. The campaign of opposition by farmers and their supporters is now an established chapter in state history. Lore about the “bolt weevils” who toppled giant steel transmission towers at night has been passed on as a compelling image of rural people’s resistance against power companies and state authorities. The events of the powerline struggle amount to a noteworthy episode of populist protest, and this book remains that story’s most thorough telling.

The fact is, though, that today we probably read this book mostly because we know that one of the story’s tellers, an activist college professor a the time, Paul Wellstone, eventually became a U.S. senatorâ??a senator who would make unique and dramatic contributions to our country’s history an dpolitical life in his far-too-brief career. After cowriting this book, Paul went on to participate in, teach about, and write on other Minnesota and national political struggles throughout the 1980s. Then, in 1990, he was elected to the U.S. Senate. He promptly carried the kind of fight and values described in the book straight to Washington, where he shook things up for twelve years and rocked the system right up until the terrible day that his life was tragically cut short.

As I’ve said before, Paul Wellstone was my best friend in the Senate. He truly was the soul of the Senate, and no one ever wore the title “Senator” betterâ??or used it less. Staff and citizens alike called him Paul, and he wouldn’t have had it any other way.

Paul was always the same person. As political scientist and teacher, as community organizer, or as representative of the citizens of Minnesota, his method was based in direct and personal connection to people. He blurred the distinction between his life projects. He organized and agitated in the classroom. He encouraged and gave strategic advice to the subjects of his social science interviews. He taught from the floor of the U.S. Senate.

Paul was deeply committed to his political principles. But he was also a keen listener and respected the motivations of the people he spoke with, including those who differed from him. People felt this, and it helped him excel at all three of his professional callings.

Paul worked with a true partner on this book, Barry “Mike” Casper, a physicist colleague and friend at Carleton College who was every bit Paul’s equal when it came to political passion. Mike’s grasp of technology and energy policy helped frame what farmers saw as a fight rooted i their moral obligation to the soil and future. At a key moment during this period, Mike joined one of the protest leaders, Alice Tripp, on a ticket to try to deny the Democratic-Farmer Labor nomination to incumbent governor Rudy Perpich. They gained a suprising 17 percent of the primary vote. Mike became one of Paul’s first staffers in Washington and drafted an alternative national energy policy bill when Paul joined the Senate Energy Committee.

Powerline is about power, both electrical and political, and about justice. It is also a study of political processâ??not the way textbooks say it works, but the way it really happened in Minnesota. Power companies, cooperatives that were supposed to be run by and for their rural customers, used eminent domain and plotted their line according to a dry, numerical “avoidance rating” system. The system assigned the lowest avoidance value to farms. How out of touch could they be? No matter: farmers who resisted the companies’ plans found the process rigged and their state government tilted against them. Local law enforcement was reluctant to use force against those engaged in peaceful civil disobedience, but the bureaucratic hearings would not go farmers’ way. They didn’t win their fight, even though more than 60 percent of Minnesotans supported their cause. They were outmatched by the power companies’ lawyers and technical experts. In the end, state government and the courts took the companies’ side.

The story’s outcome is sadly familiar, but its telling is often inspiring. Many of the accounts here are firsthand, and some are humorous. Hog manure was put to tactical use on more than one occasion. Bullets and deadly dangerous anhydrous ammonia were also used, however, and both sides of this fight considered the stakes to be very high. The interviews that make this book possible could only have happened after the authors gained deep trust from farmers, some of whom at minimum had knowledge of serious illegal acts.

The farmers’ struggle did affect energy policy in the state, though not immediately. Their protests raised questions about a paradigm of remote, unaccountable decision making that led to huge, centralized power production and lines that disrupted the landscape. These questions are around today, and Minnesota, like my home state of Iowa, has since done much to involve communities in energy planning, as well as to diversify sources to include more renewables such as wind and biofuels.

The powerline fight also prefigured later political events. It may even have helped rekindle a Midwest tradition of populist prairiefire that connected urban and rural dissatisfaction. Paul and Mike devoted much of their time and talents in the 1980s to the family farm movement, even while they were deeply immersed in peace activism, organizing the poor, and working on other issues that mobilized the Twin Cities’ large progressive community. Paul helped bring students and labor union members from metropolitan areas to support striking P-9 meatpackers in Austin, Minnesota. By 1988, he was Minnesota chair of Jesse Jackson’s run for the Democratic presidential nomination, and the network he developed in that campaign became the foundation for the ground game of his famous outsider race to the Senate two years later.

Senator Paul Wellstone didn’t emerge suddenly or magically from the powerline fight in west central Minnesota. But he didn’t come from nowhere, either. His approach to politics resonates clearly as he helps to tell the story in this book. That makes it a story worth remembering.

Leave a Reply