Friday’s North Carolina Voting Rights Case

July 31st, 2016

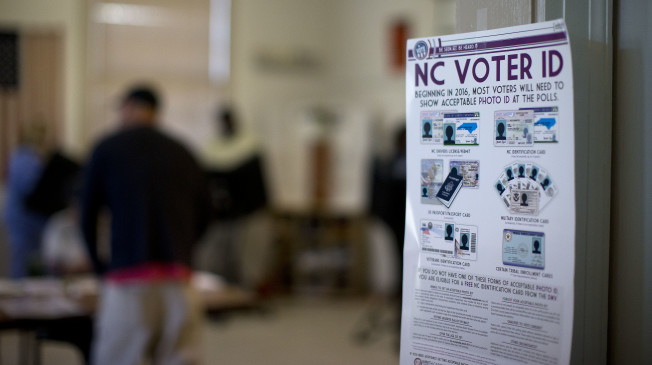

(PHOTO: Andrew Krech/News & Record via AP) MANDATORY CREDIT

(PHOTO: Andrew Krech/News & Record via AP) MANDATORY CREDIT

(see also post above, where Wisconsin’s election law was also tossed)

For those concerned with voting rights, here’s Friday’s decision of the U.S. 4th Circuit Court of Appeals finding that North Carolina’s election law intentionally discriminated against African-American voters, and that it violated the Voting Rights Act and multiple provisions of the U.S. Constitution:

North Carolina – Voting Rights – Court Files 16-1486; 6-1469; 16-1474- 16-1529

Well worth a read to understand the lengths North Carolina legislators went to disenfranchise voters, African-American voters. A few tidbits:

But, on the day after the Supreme Court issued Shelby County v. Holder, 133 S. Ct. 2612 (2013), eliminating preclearance obligations, a leader of the party that newly dominated the legislature (and the party that rarely enjoyed African American support) announced an intention to enact what he characterized as an “omnibus” election law. Before enacting that law, the legislature requested data on the use, by race, of a number of voting practices. Upon receipt of the race data, the General Assembly enacted legislation that restricted voting and registration in five different ways, all of which disproportionately affected African Americans. (p. 10)

… In addition to this general statutory prohibition on racial discrimination, Congress identified particular jurisdictions “covered” by § 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Shelby Cty., 133 S. Ct. at 2619. Covered jurisdictions were those that, as of 1972, had maintained suspect prerequisites to voting, like literacy tests, and had less than 50% voter registration or turnout. Id. at 2619-20. Forty North Carolina jurisdictions were covered under the Act. 28 C.F.R. pt. 51 app. (2016). (p. 12)

After Shelby County, with race data in hand, the legislature amended the bill to exclude many of the alternative photo IDs used by African Americans. Id. at *142; J.A. 2291-92. As amended, the bill retained only the kinds of IDs that white North Carolinians were more likely to possess. Id.; J.A. 3653, 2115, 2292. (p. 15).

While the Supreme Court has expressed hope that “racially polarized voting is waning,” it has at the same time recognized that “racial discrimination and racially polarized voting are not ancient history.” Bartlett v. Strickland, 556 U.S. 1, 25 (2009). In fact, recent scholarship suggests that, in the years following President Obama’s election in 2008, areas of the country formerly subject to § 5 preclearance have seen an increase in racially polarized voting. See Stephen Ansolabehere, Nathaniel Persily & Charles Stewart III, Regional Differences in Racial Polarization in the 2012 Presidential Election: Implications for the Constitutionality of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 126 Harv. L. Rev. F. 205, 206 (2013). Further, “[t]his gap is not the result of mere partisanship, for even when controlling for partisan identification, race is a statistically significant predictor of vote choice, especially in the covered jurisdictions.” Id. (p. 28).

While it is of course true that “history did not end in 1965,” id., it is equally true that SL 2013-381 imposes the first meaningful restrictions on voting access since that date — and a comprehensive set of restrictions at that. Due to this fact, and because the legislation came into being literally within days of North Carolina’s release from the preclearance requirements of the Voting Rights Act, that long-ago history bears more heavily here than it might otherwise. Failure to so recognize would risk allowing that troubled history to “pick[] up where it left off in 1965” to the detriment of African American voters in North Carolina. LWV, 769 F.3d at 242. (p. 32).

Leave a Reply