Siting solar? Here’s how!

December 14th, 2020

This just appeared, a rational siting notion for a solar project — site it on an abandoned mine site, which because of the prior activity, has transmission ready and waiting. Well, DOH!

A Bright Future: Former U.P. Mine Site to Be Redeveloped as 300-Acre Solar Array

They’re just using a portion of the mine’s land, it could, and SHOULD, be much larger:

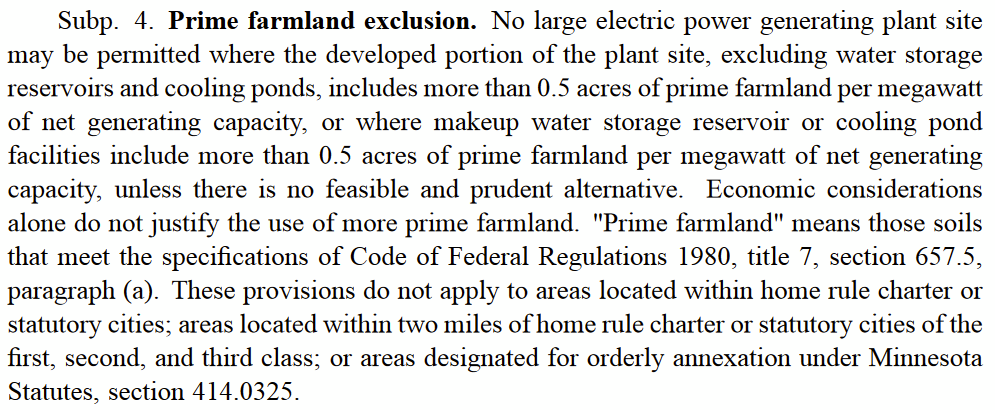

Minnesota has a prime ag land exception for power plants:

Wisconsin has a brownfield law, which, at WI’s Public Service Commission permitting deliberation for the Badger Hollow Solar docket, Commissioner said they just ignore that!

Wisconsin brownfield in WI CPCN statute:

https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/statutes/statutes/196/491/3/d

(d) Except as provided under par. (e), the commission shall approve an application filed under par. (a) 1. for a certificate of public convenience and necessity only if the commission determines all of the following: … 8. For a large electric generating facility, brownfields, as defined in s. 238.13 (1) (a), are used to the extent practicable.

And the definition of “brownfield” in 238.13 (1) (a):

238.13 Brownfields grant program. (1) In this section: (a) “Brownfields” means abandoned, idle or underused industrial or commercial facilities or sites, the expansion or redevelopment of which is adversely affected by actual or perceived environmental contamination.

****************************************

A Bright Future: Former U.P. Mine Site to Be Redeveloped as 300-Acre Solar Array

By Ben Meyer• Dec 10, 2020 ShareTweetEmail The former Groveland Mine site. In the foreground, concrete foundations and silos are remnants of the processing plant. Beyond them, the tailings areas will serve as land for a new solar array. Credit Dan Dumas/Kim Swisher Communications

On a sunny day last week in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Kevin Sundholm picked up a small handful of marble-sized pellets of iron ore from the ground. Pelletized iron ore left over from the days of production at the Groveland Mine. Credit Dan Dumas/Kim Swisher Communications

“Those pellets would go through there and they would get baked,” he said, gesturing at the abandoned foundations of the former Groveland Mine complex near Felch, in Dickinson County.

“You can see the remnants up on top of the silos there,” Sundholm said.

He knows the lay of the land. He worked here more than 40 years ago. Kevin Sundholm, who worked at the Groveland Mine almost 40 years ago. Credit Dan Dumas/Kim Swisher Communications

For decades, the complex produced these pellets from the ore taken from the adjacent open-pit mine. Loads of pellets were taken by train to Escanaba, then by ship to steel mills in Ohio.

“Basically, there [were] 90 to 100 cars of ore pellets that went out of here every day,” Sundholm said. “This place ran 24/7/365. They put out a good [iron ore] pellet, a specialized kind of pellet here that was used in the steel mills.”

But that all ended abruptly in January 1981.

Today, the site is just one of countless decommissioned iron ore mines in the Upper Peninsula.

But the future of the former Groveland Mine is different than the rest.

It’s about to start producing something much cleaner and more modern: solar power.

The state of Michigan hopes Groveland will be one of the first in this trend of redevelopment. The rudimentary mining operations in 1909. Credit Stu Belheumer, from the book Felch Township 1878 to 1978 Centennial

The first small-scale mining started here in 1891, according to Felch Township 1878 to 1978 Centennial, a book edited by Beatrice M. Blomquist.

In the 1950s, the major extraction and shipping of iron ore started.

Kevin Sundholm remembers the exact day he started work at the mine: September 15, 1976.

“At that time, this was the job to have in Dickinson County,” he said. “This job here was the job to have, because of the pay, the benefits, the vacation, just everything. It was the place to work.”

He also remembers the day his supervisor told him he was out of a job, just five years later.

“I said, ‘Oliver, what’s the problem? What’s going on?’ He said, ‘Effective next Friday, this mine will be shut down temporarily.’ Bang. That was a Thursday or Friday. One week later, there she was. They shut her down,” Sundholm said.

The Groveland Mine never reopened. Hundreds of people lost their jobs, and it’s been idle since 1981.

“It was a sad thing. It was a sad, sad thing when it closed,” Sundholm said. “A lot of people lost their livelihood here, and it was a blow to this whole county.” Remnants of infrastructure from the Groveland Mine. Credit Dan Dumas/Kim Swisher Communications

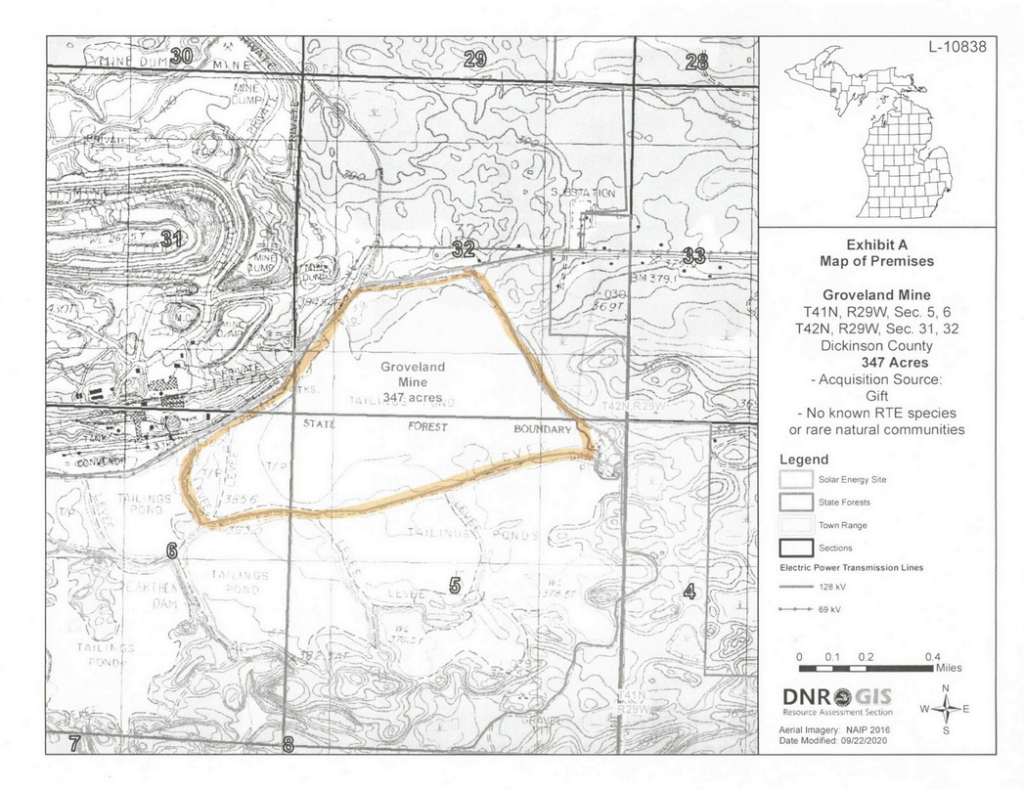

Some of the old mine infrastructure still stands. But the Michigan DNR, which now owns parts of the property, has a new vision for its future, a first-of-its-kind major solar array on DNR land. A map of the area. The circled portion is the target for the solar array. Credit Michigan DNR

“This is kind of a pioneer,” said Matt Fry, a DNR Land Use Program Leader. “Now, we’re talking, with this one, when it’s built out, should be over 300 acres.”

The array will go on the old mine tailings area, a piece of land just southeast of the pit.

The DNR has never tried anything like it on this scale before, but under the direction of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, the state is being more proactive in developing renewable resources.

“We’re recognizing that we have an issue with climate change,” Fry said. “For the greater good of the citizens of the state, we need electricity.” The tailings area of the Groveland Mine site. The Michigan DNR and Circle Power plan to develop this area into a solar array.

Circle Power is in charge of developing the solar array on the site. The company admits solar in the U.P., where there is sometimes more snow than sun, may seem counterintuitive.

But Jordan Roberts, a Circle Power founder, said advances in the field have made it attractive.

“When we heard this opportunity, and the opportunity to use underutilized land to create a solar project, we got really excited,” he said.

The transition to more solar power will directly help people living locally, according to Roberts.

“In the Upper Peninsula, power costs are quite high,” he said. “There are all sorts of folks looking for ways to get those costs down.”

If the permitting and development go just right, the former mine site could be generating solar power by 2023. It could power 4,000 homes. The open pit at the Groveland Mine. After production stopped, the pit filled with water.

At the site, Kevin Sundholm isn’t the only one with memories of and ties to the mine.

Bob Mattson is Sundholm’s cousin and the Felch Township Supervisor. He’s lived here his entire life.

“It really took off, I think it was 1950 or ’51. That’s when the pellet plant was built. My dad built those silos right there,” Mattson said.

The Township of Felch includes most of the area of the planned solar array.

“I thought it was a great idea. It’s going to create some tax revenue for us, personal property tax, which is a good thing,” Mattson said. These tracks haven’t seen a train full of iron ore in nearly 40 years. But a nearby solar array could be operating by 2023.

Many of Sundholm’s former mine coworkers won’t be around to see the day solar power is generated at the former mine site.

“A lot of the old-timers are gone,” he said.

It’s been nearly forty years since the day the mine closed for good. But, in just a few years, solar panels will start making power for the Upper Peninsula at the very same place.

“I think it’s a great idea,” Sundholm said. “Today it’s sunny. That sun is shining. If those solar panels are out there today, we’re making clean energy.”

Leave a Reply