Muller: Time to think about…

August 23rd, 2015

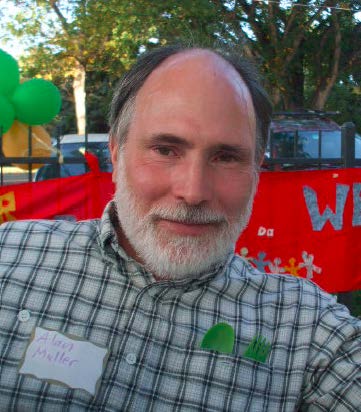

Commentary by Alan Muller, Green Delaware, in today’s Delaware State News:

Commentary: Time to think about Delaware’s Peterson, Coastal Zone Act

So what about this Coastal Zone Act? What makes it special and worth preserving.

Alan Muller is Executive Director of Green Delaware.