Tuesday 12/1 – PPSA Annual Hearing

November 29th, 2015

Here we go again, this year’s Power Plant Siting Act Annual Hearing.

Public Utilities Commission (PUC) Docket Number: E999/M-15-785

Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH) Docket Number: 60-2500-32901

Date: Tuesday, December 1, 2015

Time: 9:30 a.m.

Location: Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, Large Hearing Room, 121 7th Place East, Suite 350, Saint Paul, MN 55101

Bad weather? Find out if a meeting is canceled. Call (toll-free) 1-855-731-6208 or 651-201-2213 or visit mn.gov/puc

Here are some prior dockets (to access the entire docket, individual comments, etc., go to :

2006 Report to PUC – Docket 06-1733

2007 Report to PUC – Docket 07-1579

2008 Report to PUC – Docket 08-1426

2009 Report to PUC – Docket 09-1351

2010 Report to PUC – Docket 10-222

2011 Report to PUC – Docket 11-324

2012 Report to PUC – Docket 12-360

2013 Report to PUC – Docket 13-965

2014 Summary Comments– Docket 14-887

Rulemaking Ch. 7829 at PUC tomorrow

November 18th, 2015

Tomorrow, the Chapter 7829 Rulemaking is going to the Commission, for approval of the FINAL rules. This rulemaking has been going on formally for over two years now in Docket 13-24 (go to NEW SEARCH and search for this docket).

Overland 7829 Comment Nov 18 2015

And some history… I’ve been concerned about this chapter for a long while, and submitted a Petition for Rulemaking over FOUR YEARS ago. Apparently that was filed in the trash:

And prior posts:

Ch. 7829 Rulemaking Comments July 20th, 2015

Stealth rulemaking — PUC’s Minn. R. Ch. 7829 July 10th, 2014

PUC’s Stealth 7829 Rulemaking Docket June 4th, 2013

PUC requests Comments on 7829 rules August 8th, 2013

Minn. R. 7829 marches on… September 9th, 2013

Clean Coal Carolers

November 15th, 2015

Someone posted the Minion Carolers, and, well, though I don’t need to get too wrapped up in these things because I AM a Christmas Carol, I remembered this from a few years back and found one (weren’t there more?_ and want to capture it while the spirit moves me:

NOTICE – PPSA ANNUAL HEARING 12/1

November 9th, 2015

Notice of the Power Plant Siting and Transmission Line Routing Program Annual Hearing

Issued: November 6, 2015

In the Matter of the 2015 Power Plant Siting Act Annual Hearing

Public Utilities Commission (PUC) Docket Number: E999/M-15-785

Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH) Docket Number: 60-2500-32901

Date: Tuesday, December 1, 2015

Time: 9:30 a.m.

Location: Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, Large Hearing Room, 121 7th Place East, Suite 350, Saint Paul, MN 55101

Bad weather? Find out if a meeting is canceled. Call (toll-free) 1-855-731-6208 or 651-201-2213 or visit mn.gov/puc

Hearing Description

The annual hearing is required by Minnesota Statute § 216E.07, which provides that:

Thecommission shall hold an annual public hearing at a time and place prescribed by rule in order to afford interested persons an opportunity to be heard regarding any matters relating to the siting of large electric generating power plants and routing of high-voltage transmission lines. At the meeting, the commission shall advise the public of the permits issued by the commission in the past year….

Note – No decisions about specific projects are made at the annual hearing.

Public Hearing Information

- Public hearings start on time.

- Arrive a few minutes early so you have time to sign in, pick up materials, and find a seat.

- Administrative Law Judge James LaFave will preside over the hearing.

- Public Utilities Commission and Department of Commerce staff members are available to answer questions about the Power Plant Siting Act processes and the projects.

- You may add verbal comments, written comments, or both into the record.

- Learn more about participating at a public hearing at http://mn.gov/puc/resources/meetings-and-hearings.jsp

- Judge LaFave will use information gathered at the public hearing and during the comment period to write a summary report for the Commission

Submit Comments

Topics for Public Comment:

- Any matters related to the site permit process for large electric generating power plants and routing of high-voltage transmission lines.

Comment Period: November 6, 2015 through January 5, 2016 at 4:30pm.

- Comments must be received by 4:30pm on the close date

- Comments received after comment period closes may not be considered

Online Visit mn.gov/puc, select Speak Up!, find this docket (15-785), and add your comments to the discussion.

If you wish to include an exhibit, map or other attachment, please send your comments via eFiling (see below) or U.S. Mail.

Please include the Commission’s docket number in all communications.

Filing Requirements: Utilities and state agencies are required to file documents using the Commission’s electronic filing system (eFiling). All parties, participants and interested persons are encouraged to use eFiling: mn.gov/puc, select eFiling, and follow the prompts.

Important Comments will be made available to the public via the Public Utilities Commission’s website, except in limited circumstances consistent with the Minnesota Government Data Practices Act. The Commission does not edit or delete personal identifying information from submissions.

Hearing Agenda

I. Introductions

II.Overview of Programs

A. Public Utilities Commission – Facilities Permitting and Public Advisor

B. Department of Commerce – Energy Facilities Permitting Unit

C. Role of Other Agencies

III. Projects Reviewed

A. Projects Permitted in 2015

B. Pending and Anticipated Projects

C. Electric Facilities Subject to Power Plant Siting Act

1. Generating Plants

2. Transmission Lines

IV. Public Questions and Testimony

V. Adjourn

How to Learn More

Subscribe to the Docket: Subscribe to receive email notifications when new documents are filed. Note – subscribing may result in a large number of emails.

- mn.gov/puc

- Select Subscribe to a Docket

- Type your email address

- For Type of Subscription, select Docket Number

- For Docket Number, select 15 in the first box, type 785 in the second box

- Select Add to List

- Select Save

Full Case Record: See all documents filed in this docket via the Commission’s website – mn.gov/puc, select Search eDockets, enter the year (15) and the docket number (785), select Search.

Project Mailing Lists: Sign up to receive notices and opportunities to participate in other dockets relating to specific projects in which you are interested (meetings, comment periods, etc.). Contact docketing.puc@state.mn.us or 651-201-2234 with the docket number, your name, mailing address and email address.

Minnesota Statutes and Rules: The hearing is being conducted according to Minnesota Statute 216E.07. Minnesota Statutes are available at www.revisor.mn.gov.

Project Contacts

Public Utilities Commission Public Advisor

Tracy Smetana – consumer.puc@state.mn.us, 651-296-0406 or 1-800-657-3782

Xcel’s new rate increase request

November 2nd, 2015

Xcel’s cost of electricity is down. Yet they want more money from us, 9.8% over the next 3 years, with the average residential customer’s 675 kW/hr bill to go up $11 a month. WHAT?

Meanwhile, last year at the legislature, the biggest of the big customers got a special rate category and special lower rates. WHAT?

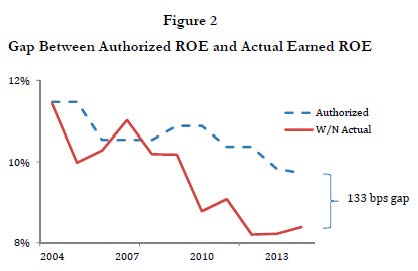

The above graph is from Chuck Burdick’s testimony — after dealing with him in the Goodhue Wind case, I couldn’t resist checking out his testimony (Application, 2A2 – MYRP).

So if Xcel Energy was authorized a certain ROE, and only earned a much lesser ROE, does that mean we should make up the difference? Also from Burdick’s testimony:

Were this “free market” the response would be that the company should contract, that there are too many cooks in that kitchen, that the capital expenses not for our use, such as this big transmission build-out, should not occur, and we should not have to pay for them.

Were this “free market” the response would be that the company should contract, that there are too many cooks in that kitchen, that the capital expenses not for our use, such as this big transmission build-out, should not occur, and we should not have to pay for them.

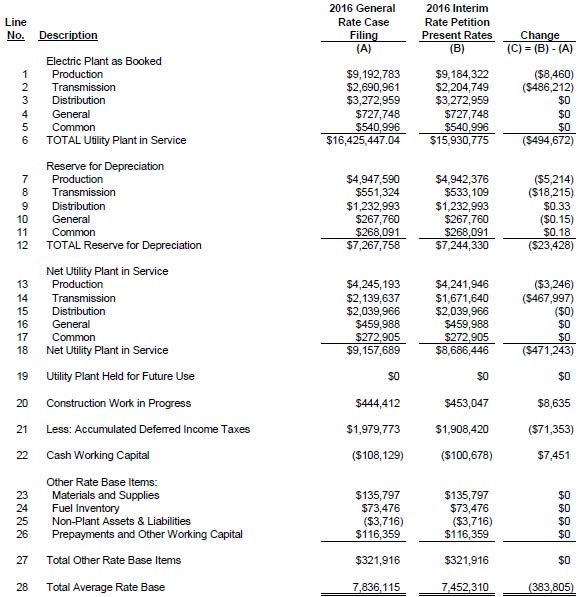

Let’s take a look at the drivers, where they’re running short — do we want to pay for this? From the Application 1:

The initial filing in this new rate case is there for the reading, dig in, I’m sure there’s something you’ll enjoy.

Just go HERE TO PUC’S SEARCH DOCKETS PAGE and search for PUC docket 15-826, opened today.

In the STrib today:

Xcel seeks 9.8 percent rate hike in Minnesota over three years