Delmarva Power to rebuild transmission in DE?

January 3rd, 2015

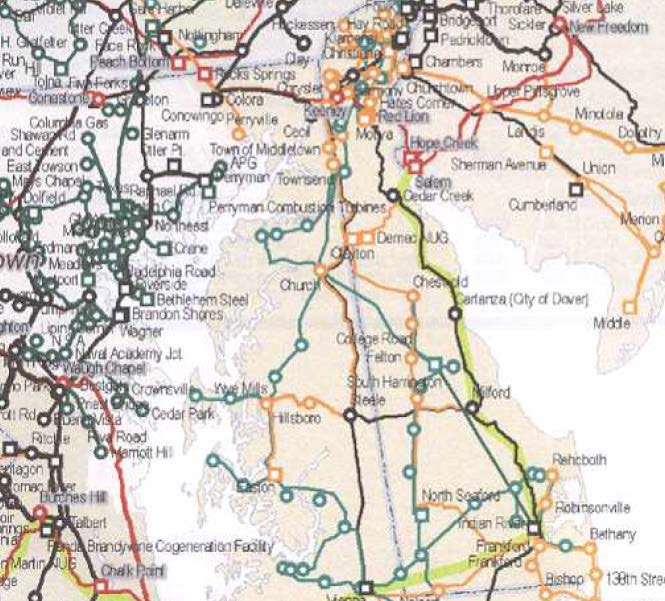

Delaware’s a small state, and it’s just the wrong shape for getting a good transmission map. Click the above one for a larger view, but it’s still hard to see. But check it out! Take a look at that black line, stretching from Red Lion down to Milford. That’s the 230 kV line that Delmarva Power wants to rebuild. If they play this as I think they will (please prove me wrong), they could use this “rebuild” to significantly increase transfer capacity, which given the withdrawal of the Mid-Alantic Power Pathway (MAPP) transmission project, that’s something to watch for.

Public meeting about transmission line rebuild

7 p.m. Wednesday, Jan. 7, 2015

Odessa Fire Company

304 Main St., Odessa, Delaware

Hosted by Delmarva Power

There’s essentially no regulation of transmission in Delaware, a fact that’s hard to believe given the impacts and power associated with transmission. This project is intended to go right down an existing easement, but the original line was built 50 years ago, and there’s been a lot of development in Delaware since then. Look at the map, and there’s a lot of development right next to this transmission line. Do you think these folks know anything about this transmission plan? Do you think anyone along that easement is getting direct notice about this???

At first glance, a couple of things occur to me.

- Rebuild? As always, I want to know the details. they say it will still be at 230 kV. Let’s have the conductor specs, particularly. How big a conductor are they using, ACSR or ACSS or higher capacity? Will they be rebuild as a single or double circuit, and will it be bundled or not? Here’s the photo of the line, photo from Snooze Urinal, and it’s as it looks to me from driving under it numerous times on the way to/fro Port Penn:

Photo from The News Journal, delawareonline.com

Photo from The News Journal, delawareonline.com

- Use of existing easement or extending beyond? In their press release, there’s something disturbing about how they say they’re going to build this thing:

So looking at this photo above, it’s facing north, the H-frames are on the east side, the monopole on the west, and the News Journal report says:

How is that possible? The H-frames have been there a long time, and rather recently they added the monopole next to it. Now now this will be “built along the eastern border of the existing right-of-way.” EH? Here’s an example, at the intersection of Port Penn Rd. and the line, the “east” is on right on this photo/map (click photo for larger version):

This is what it looks like at the road, looking down the easement with home on the left:

And here’s another example, at the intersection of Pole Bridge Rd. and the transmission lines, also on the way to/fro Port Penn, note the new subdivision roads, Waterbird Lane and Marsh Hawk Court:

Here’s another at 955 Vance Neck Rd (the road is just to the south):

Let’s keep going further south along the easement. Here are homes along Old Corbett Rd. near the intersection of Hwy. 9 — note it’s turned around to fit better, the “easterly” direction they’ll build into is the area towards the homes:

Here’s another subdivision on the other side of Hwy. 9, and the homes along Middessa Drive:

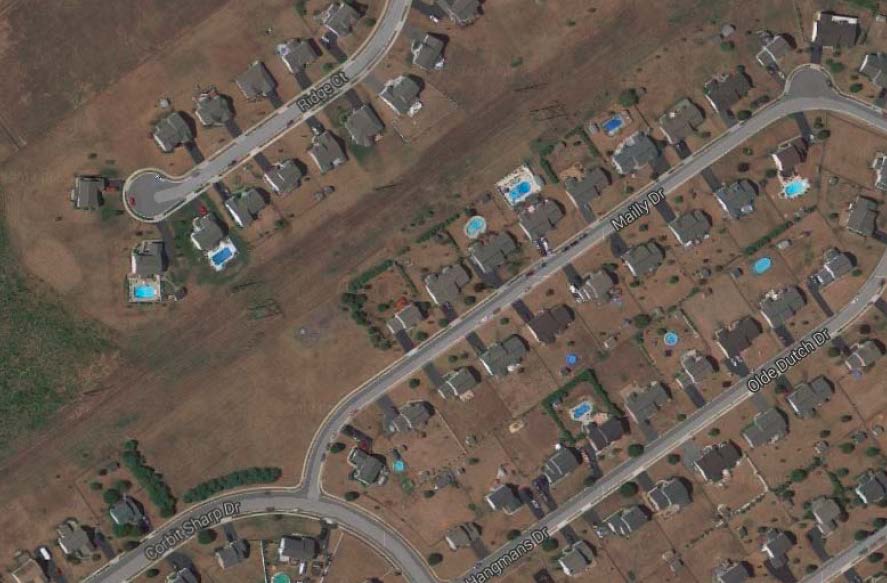

Just a little further south, where the line turns southwesterly, the line is abutted by the homes on Mailly Drive and Corbit Sharp Drive:

Here’s what that easement looks like — build this new thing on the easterly border of the easement? I think not!

And this northern Red Lion to Milford section of the transmission “rebuild” terminates at the Cedar Creek substation, technically in Townsend:

Again, do you think these folks know anything about this transmission plan? Do you think anyone along that easement is getting direct notice about this???

Here’s Delmarva’s Press Release:

Press Release 12/23/2014 – Delmarva Power Project to Benefit Delaware

Here’s the report from the News Journal:

Delmarva to brief public on transmission line rehab

The electrical spine of Delaware is set for a $70 million rehabilitation.

The utility will host a public meeting to brief the community on the project on Wednesday in Odessa.

Contact Staff Writer Xerxes Wilson at (302) 324-2787 or xwilson@delawareonline.com.

For more information:

Delmarva Power will host a public meeting at 7 p.m. Wednesday, Jan. 7, at the Odessa Fire Company, 304 Main St. in Odessa.

DE’s Bluewater Wind Project dead…

December 15th, 2011

Seems they’ve put out a press release – the market is at it again. The first US offshore wind project is going down due to lack of interest, no investors, the market for electricity sucks, so they’re cancelling the contract with Delmarva. Thanks to a little gas birdie for this heads up!

From the News Journal, a series from Aaron Nathans (I’ll be he’s glad he’s not in Wisconsin anymore!):

NRG to end Bluewater contract with Delmarva

NRG Drops Delaware Offshore Wind Farm Project

But a little more than two years later, the outlook for offshore wind and for the Delaware project “has changed dramatically,” the company said. “In particular, two aspects of the project critical for success have actually gone backwards: the decisions of Congress to eliminate funding for the Department of Energy’s loan guarantee program applicable to offshore wind, and the failure to extend the Federal Investment and Production Tax Credits for offshore wind which expire at the end of 2012 and which have rendered the Delaware project both unfinanceable and financially untenable for the present.”

Finding an investment partner has been another difficulty. “In addition, a central element of the Wind Park’s business plan, previously communicated to public authorities in Delaware, was to find an investment partner. To date the company has been unable to find a partner, despite the attractiveness of the PPA and after having approached more than two dozen prospective investors over the course of several months,” NRG said.

The company said its next steps would be to close its Bluewater Wind development office but preserve its options by maintaining its development rights and continuing to seek development partners and equity investors. “If and when market conditions improve and the company is able to find partners, NRG will look to deploy the Wind Park and explore other viable offshore wind opportunities in the Northeast.”

Alan Muller featured in Delaware Today

September 19th, 2011

Alan Muller ‘s office in Lake Itasca Park

And at a Rock-Tenn Burner Fest in St. Paul, being introduced by Nancy Hone, Neighbors Against the Burner:

Here’s a profile of Alan that was published in Delaware Today:

Alan Muller takes no prisoners.

His wrath spares few of those in power. Here’s a sampling:

Of the State Chamber of Commerce: “Probably the biggest single foe of the environment in the state.”

His scorched-earth style can elicit bitter backlash. Says John Taylor, senior vice president of the State Chamber of Commerce: “Alan Muller is great at name-calling but lousy on getting his facts right. Mr. Muller attacks anyone who doesn’t agree with him 100 percent. And his narrow, misguided and misanthropic vision is well-known to those in Delaware who truly care for the environment. In fact, the Delaware State Chamber of Commerce has been an active partner in bringing clean energy to Delaware. The latest example of this being the Bloom Energy decision to come to Newark.” While Taylor no doubt expresses what many would like to, other Muller targets chose a more circumspect response. Markell, who gets high marks from many enviros, would say only, “Alan Muller believes strongly in his causes and makes himself heard.” Chris Coons’ office declined to comment. Another Muller target, Debbie Heaton, of the Sierra Club and The Nature Conservancy, says merely that she does not have “happy memories” of working with him.

The official response to Muller is often to ignore or avoid him. That’s understandable, according to John Flaherty, another well-known Delaware activist. “Power hates and marginalizes people who are right, like Alan, because they reveal that the powerful use their positions for themselves and for the interests they serve. And once someone has been banished to the margins, the powerful can rely on the conditioned habits of the public. After all, don’t we all know that anyone on the margins is, by definition, unacceptable?”

According to Muller and some of his supporters, he’s been mistreated and harassed over the years—especially by New Castle County government, which has cited him for many violations at his Port Penn home, a historic building he purchased for about $15,000 (supplemented by a state grant) with the agreement to upgrade it. Muller says the price of the house and its central location between Wilmington and Dover cancels out environmental considerations like the three nearby nuclear reactors, the Delaware City Refinery and other major polluters.

In 2001 Baker had him arrested for “graffiti” and “criminal mischief” after Muller posted warning signs on an open channel carrying raw sewage through a Brandywine Park picnic area. In 2005 he and John Kowalko, then director of the ACORN utility campaign, now a state representative, were ejected from Legislative Hall during a House Energy Committee hearing. When they weren’t allowed to speak, Muller and Kowalko tied gags to their mouths. That incensed then-Rep. Robert Valihura, chairman of the committee, who ordered Capitol Police to remove them.

Calling it “death by a thousand cuts,” Muller says “harassment in the past few years has been relentless.”

Meanwhile, he laments the “plantation mentality” that pervades the state—“the reluctance of people to say anything challenging or critical,” including the media and other environmental organizations. The latter, he says, have been bought off or bullied into submission by those in power. “Other states are less hostile,” he says.

As a result, the somewhat rumpled 61-year-old, nursing “aching feet and a creaky back,” may leave Delaware, perhaps for Minnesota, where his soul mate, Carol Overland, is an energy consultant and lawyer. He spends about half of each year working for environmental groups in several states, at fees exceeding the small income he takes from Green Delaware.

As the most prominent activist in the state’s recent past contemplates taking his leave, it seems an appropriate time to examine his legacy—and his motivation.

For someone so passionate about it, Muller came relatively late to the environmental movement. But the seed was planted early. He grew up in Welshire, a North Wilmington suburb, living with his parents and a brother, who was a year younger. His father, Joseph, was a DuPont manager.

“I’m not saying my father was a bad guy,” Muller says, “but he reflected the values of the chemical industry at the time, and his proudest achievement was bollixing up an EPA effort to regulate sulfuric acid plants. He and other DuPonters went to Washington in the ’60s and testified that (regulation) was unreasonable, impossible and too expensive. As a kid, I thought about it and decided I kind of didn’t agree. I remember thinking the EPA could have gotten the technical details wrong, but it was hard to disagree with the concept of reducing pollution.”

(Of his relationship with his late parents, Muller says: “It had its ups and downs. I’d think my activism was part of it. They would have liked a picket-fence Republican son and grandkids.” Married once, briefly, Muller has no children.)

Fast-forward several years. Muller drops out of UD after his junior year (eventually earning a social sciences degree), goes on to several jobs, then finds himself working as a consultant for, ready? DuPont!

As a technical writer for the company’s engineering department, he says he worked with people who were involved in environmental cleanup and who also lobbied against stricter regulations. “I began to see how it worked from the inside. After several years of pumping out this rhetoric about ‘clean and green’ and don’t regulate us because we do the right things, when Reagan came in, all the company’s pro-environment rhetoric basically stopped, because they felt, ‘Now our guy is in charge.’”

While acknowledging that DuPont paid and treated him well, Muller says, “I began to not like the way they spent so much energy on bullshit and propaganda and suborning the regulatory process rather than just knuckling down and fixing the problems. I didn’t like being involved in that.”

And so an environmental advocate with the passion of a convert was born.

Casting about among the state’s enviro groups, he chose the Sierra Club, where he became conservation chairman. Soon his blunt style and disagreements with some club policies and members got him kicked out—via registered letter.

So, in 1995, he formed Green Delaware, recruiting longtime activists Jake Kreshtool, Ted Keller and Frieda Berryhill. Essentially a virtual organization with an email list of about 3,000 and fueled by Muller’s data-filled, aggressive newsletters, it quickly became the state’s most active—or at least most annoying—environmental group, and he gained a reputation for fact-based arguments that often irked opponents.

The 93-year-old Kreshtool, a labor lawyer and former candidate for governor, admits Muller “isn’t much on social skills,” and can be irritating, “But he’s always polite, and his testimony was determinative in many, many cases involving air pollution.”

Much of Green Delaware’s support comes from an annual $10,000-$15,000 grant from the New Jersey Environmental Federation and Environmental Endowment for New Jersey. The grant recognizes Green Delaware’s work to limit water pollution, particularly in the Delaware River. Jane Nogaki, founding chair of the endowment, says Muller “is at the top of Delaware environmental groups. He can be confrontational without being belligerent, his arguments are well-grounded, and he asks questions rather than making accusations.”

Muller clearly has scored victories—a ban on industrial incinerators probably is his most significant—but most observers agree he could have accomplished much more with a less rigid approach. “Alan rarely declares victory,” says Flaherty. “What I would consider victories in a lot of cases he considers defeats.”

Bill Zak, of Citizens for Clean Power in Sussex County, understands Muller’s attitude. “He knows that conciliation often means things getting dropped in a drawer and forgotten.”

Flaherty and Nancy Willing, author of the liberal “Delaware Way” blog, exemplify another Muller trait: burning bridges.

Flaherty calls Muller “an incredibly bright man who has made environmentalism mainstream in Delaware,” then adds, “Alan has not spoken to me since January of 2006.” According to Muller, “John stabbed me in the back” during his campaign against incinerators.

Willing, also a Muller fan, says he cut her off when he perceived that she sided with the authorities in his dispute over upgrades to his Port Penn home.

Due in part to this penchant for severing ties and his prickly style, Muller has no prospective successor as director of Green Delaware. Kreshtool, Keller and Berryhill are all 80-plus, other allies have died, and younger people haven’t stepped forward.

“In my arrogance,” says Muller, “I thought if we set an example of being smarter, of having more principled behavior than other enviros, it would rub off. Ain’t happening. Maybe it’s my lack of leadership ability.”

If he leaves, Muller and others agree that Green Delaware will probably die, an event that has his foes rubbing their hands in anticipation. For others, like Jane Nogaki, it will be a great loss.

“Today, environmental groups are using social media to spread their message,” she says, “but there’s no substitute for local, grass-roots action. And that’s what Alan always did, standing up against the giants of industry and holding politicians accountable.”

Delaware’s O’Donnell… OH MY DOG!

October 20th, 2010

We’ve been in Minnesota since late April, thankfully, because if I were in Delaware right now, it’d be hard to not flee for the border. So is Alan going back to vote? Chris or Christine, either way Delaware loses…

Listen to the guffaws and watch her expression, she is clueless, utterly clueless, what a nutwad:

It’s snowing again… another TWO FEET!

February 10th, 2010

My world has turned black and white… here’s the view out the door, the tent for the airplane buckled this morning. We had to go out and get fuel oil for the boiler and gas for the tractor and the roads haven’t been plowed from last weekend’s storm, and here we are now smack dab in the midst of another. The governor has shut down the state, again… and meanwhile, tomorrow at 2 p.m. the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities is making its decision on the Susquehanna-Roseland, delayed from today because of the storm. Well, it’s gonna be storming all day, so I don’t think that this one day will make a difference, other than those of us coming from a distance will probably have a harder time because they’ll be another foot and a half of snow.

Our little tent roof wasn’t the only one collapsing. It could be a lot worse. Schools, big boxes all over Delaware, and even the Townsend Fire Company roofs have collapsed:

Fair Use from The News Journal/ESTEBAN PARRA

Houses too:

And then there’s the Smithsonian warehouse:

… and more view out the window back door — those crab pots aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. Just so that tree doesn’t come down on the van: