On Bakken oil in STrib…

December 16th, 2014

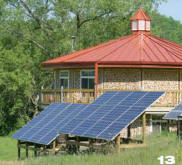

Alan Stankevitz walks the walk, and while his solar system powers his home, he tracks developments in oil transport on his DOT-111 Reader site. In this STrib op ed, he exposes the truth about “regulations” ostensibly to deal with volatility of Bakken oil: “The bottom line is that the limit has been set so high by North Dakota that the mandate is toothless.”

Bakken dangers: Both the oil and the rail

Consider these numbers. Let’s dedicate ourselves to ending the smoke-and-mirrors game.

• Crude oil from the Gulf of Mexico has a RVP psi of approximately 3.

• For crude oil from the Eagle Ford shale formation in Texas, that number is approximately 8.

• For gasoline, it’s approximately 9.

• The Lac-Mégantic oil-train explosion in Quebec had a tested RVP psi just above 9.

• Bakken crude oil typically has a RVP psi between 11.5 and 11.8.

So how much oil travels through Minnesota per day on these deficient DOT-111s?

And another along the same lines, by Lisa Westberg Peters:

New Bakken volatility standards are pointless

- Article by: LISA WESTBERG PETERS

- Updated: December 15, 2014 – 6:45 PM

The explosion risk still exists, which emboldens pipeline supporters — but why must our choices be so dismal?

(Photo: Paul Chiasson • The Canadian Press/AP file,)A large swath of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, was destroyed and 47 people were killed in July 2013 when a train carrying Bakken crude oil derailed, sparking several explosions and forcing the evacuation of up to 1,000 people.

(Photo: Paul Chiasson • The Canadian Press/AP file,)A large swath of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, was destroyed and 47 people were killed in July 2013 when a train carrying Bakken crude oil derailed, sparking several explosions and forcing the evacuation of up to 1,000 people.++++++++++++++++++++++++

I’ve seen Bakken crude oil as it comes out of the ground. It was surprising in several ways: It was almost green, quite fluid and downright fizzy with natural gases. It’s the high gas content that makes Bakken shale oil so explosive.

When the state of North Dakota established new limits on vapor pressure last week for the oil shipped out of the state, my first reaction was relief. Flammable liquids with lower vapor pressures are less volatile. We’ve seen several explosive rail accidents in recent years involving Bakken oil; an oil train derailment last year in the small Quebec town of Lac-Mégantic killed 47 people and flattened its downtown. I was pleased that regulators were addressing this problem.

But when I took a closer look at the numbers, I felt more dismay than relief. Even if oil producers exceed the regulators’ demands — and regulators say they often do — Bakken crude will still be explosive.

The appropriate comparison seems to be gasoline.

Lynn Helms, head of the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources, said the new vapor pressure standard of 13.7 pounds per square inch (psi) would make Bakken crude no more volatile than the gasoline we put in our cars every day.

In March, an investigation by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada concluded that the Bakken oil in rail cars at Lac-Mégantic was “as volatile as gasoline,” but the vapor pressure was measured at 9 to around 9.5 psi. In other words, the Bakken crude that exploded in Lac-Mégantic was less volatile than what North Dakota regulators are demanding now, and it still exploded.

In a New York Times article last week, Clifford Krauss reported: “Once the rules are in force early next year, transported North Dakota crude oil will have a similar volatility to that of automobile gasoline, which should decrease the risk and size of any fire that might occur once a rail car is punctured in an accident, according to state regulators.” His story never mentioned the findings of the Canadian government.

Why wasn’t this New York Times reporter more skeptical of the assurances of North Dakota oil regulators, especially after the recent New York Times revelations about the leniency of regulators toward the oil industry?

The new vapor pressure standard announced last week is pointless. We will still face danger from exploding oil trains.

This disturbing fact tends to encourage pipeline supporters. Pipelines are safer, they say. In the past, oil transported by pipelines has tended not to explode and kill people; instead it spills and contaminates streams, lakes and aquifers. If you value people’s lives over clean water supply, in the short term, pipelines seem better.

But why do we have to make such lousy choices to keep our domestic energy boom rolling — to keep workers working and our dream of energy independence alive? Let’s do everything we can to encourage the other domestic energy boom, the wind and solar boom, that has already begun and that survives today despite many obstacles, including national policies that still encourage fossil fuel, yesterday’s energy source. If we were to place a price on carbon tomorrow, we would not need as many pipelines and we would be able to reduce the number of oil trains passing through our neighborhoods.

Climate experts urge us to leave much of the world’s remaining fossil fuel, including Bakken crude, in the ground. If we do as they advise, we will disrupt job markets and be forced to rethink the way we do almost everything. Why should we voluntarily face such disruption? One very good reason: We already face the prospect of pervasive disruption posed by a changing climate. It’s far preferable to take well-designed and systematic measures to control disruption than let disruption control us.

Lisa Westberg Peters is the author of “Fractured Land: The Price of Inheriting Oil” (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2014). She lives in Minneapolis with her family.

Leave a Reply